How do operators make money on retirement villages?

Retirement villages have shaken off their reputation as homes for the wibbly and wobbly.

Unit prices are often over $1 million in some of the swankier villages where residents have access to a pool, cinema, cafe and community rooms for drinks and social gatherings.

But we can’t forget reality.

Even for the active, these are delicate end-of-life housing decisions. And there’s one very real statistic which doesn’t appear in village marketing material: the average tenure is seven years.

I’m not talking about those in a care suite – their average is two years. These statistics are important.

Back in 2017, one sharemarket analyst referred to the pricing model of the big-six operators as “the beautiful model”. He was basking in shareholder heaven.

Operators often speak of “acceptance” and “good understanding” of their product to investors and when lobbying politicians.

But facts and fairness are not the same thing. Just because a lawyer can explain the features, doesn’t mean a resident has choice or can weigh up value for money or suitability.

So how much money are they making?

Operators have performed a basic restructuring of a housing transaction.

First, the purchase of the unit (via a licence fee) and second, the deferred payment for village facilities. The two parts have been swept into one legal wrapper. The concept is practical.

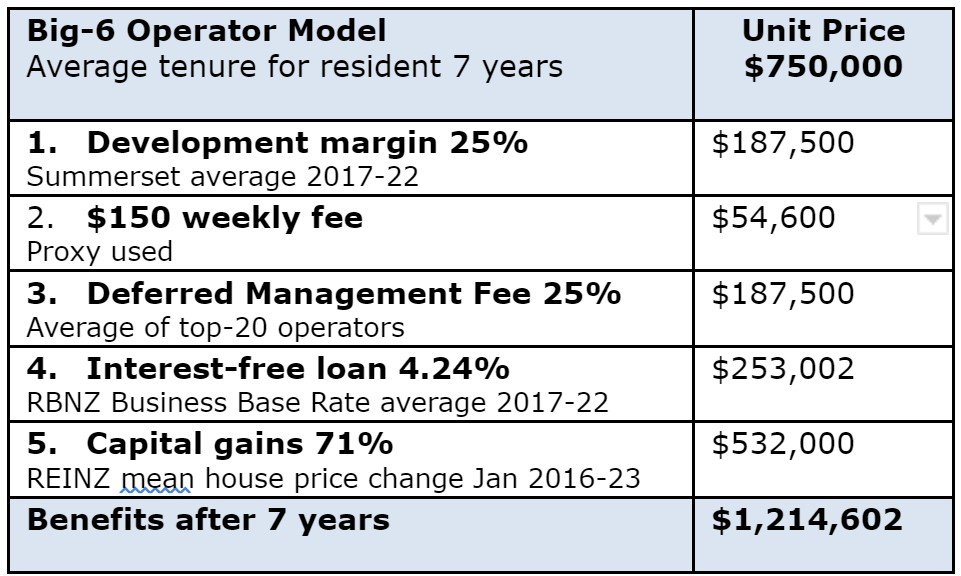

My assessment of a new $750,000 unit is operators are earning revenue and benefits over the seven-year average tenure of $1.2m ($173,000 annually). They’ve earned this without paying for the unit.

These are super-profits. Let’s be clear, profit is a good thing. Making expensive choices is also fine, but this sort of money is stratospheric and can only occur when the economic norms which prevail in a competitive market with equal power have failed.

What we have is mispricing.

Let’s start at the beginning:

1. Development margin 25%

Land, construction, infrastructure costs, head-office costs and interest on borrowed money is capitalised into the price of a unit. In the 2022 accounts for Summerset, their profit margin was 29.7%. For Arvida in 2023 it was 20%.

2. $150 weekly fee

This pays for things like maintenance, gardening, alarm bell and buildings insurance. Over seven years, that’s $54,600.

Items one and two involve no restructuring and appear commercial. The house might be in a different legal wrapper, but in substance it replicates homeownership. The restructuring occurs below.

3. 25% deferred management fee

The cost of using village facilities is deferred until death or exit. At $187,500 on a $750,000 unit, it goes without saying profit margin and the time value of money is added in.

That’s teeth-grittingly expensive, but what rubs is the fee accrues in full after only four years, not the seven-year average lifespan. In addition, every resident pays the same amount, regardless of living in the village four years or 14 years.

Some families are making a huge transfer of wealth for the benefit of other families. Housing is not an insurance product and there’s no social justification for not paying for use via an annual fee.

This isn’t a random risk. Those who move in at an older age or with health conditions are facing a certain penalty. Lawyers can disclose this but can’t offer a solution. Their client capitulates due to need.

Operators are not made to include warnings or alter their model to give all residents a fair financial outcome. There’s more profit with higher churn and no preventative legislation.

4. Capital gains 71%

The legal wrapper keeps ownership with operators. Against economic norms and substance, over $500,000 of gains are banked in the financial accounts when the next resident purchases a licence.

It's important to remember gains and losses are not a zero-sum game. Due to probability, their pricing in a structure is positive when a mathematical model is used.

For operators to keep a small slice of gains, they need to agree to take all the losses. Some argue repeating these gains is unlikely. That’s untrue over the long term and views on the payoff size are not relevant to fair pricing.

Others argue their residents don’t want property market exposure. That’s absurd misinformation when the risk sits with family and intergenerational wealth transfer is crucial, given housing affordability issues.

5. Interest-free loan 4.24%

Residents pay for a unit without owning it. Operators record this in their annual accounts as an interest-free loan.

If economic norms prevailed the loan would be fair, as consideration for the right to occupy. But the loan and gains have not been split between the parties, nor valued and restructured.

Operators simply take both. They’re able to fund new-build units with no borrowing cost, while retaining all the upside in the asset the resident purchased. It defies financial gravity and this benefit has been put in the table to make that point.

The legal wrapper and red flags

Fairness and value for money shouldn’t be altered by legal “form”. While the occupational rights agreement allows cashflow restructuring, it’s been misused.

The product is highly unsuitable on a financial level for many residents, in a health- and age-driven market which is not random.

Keeping capital gains was never essential to this business model, due to their unpredictability. I believe they were a bi-product of the structuring that fell neatly into operators’ laps. They’re now entrenched in a belief their form of ownership overrides the substance of the agreement.

No-one argued – certainly not shareholders or analysts. Residents caved in, based on need and resignation that things would never change.

A full report ‘Analysis of Retirement Village Costs’ can be viewed at www.moneytips.nz. Readers should always seek specific independent financial advice appropriate to their own circumstances.